What the Smart City Means for Future Airports

Share

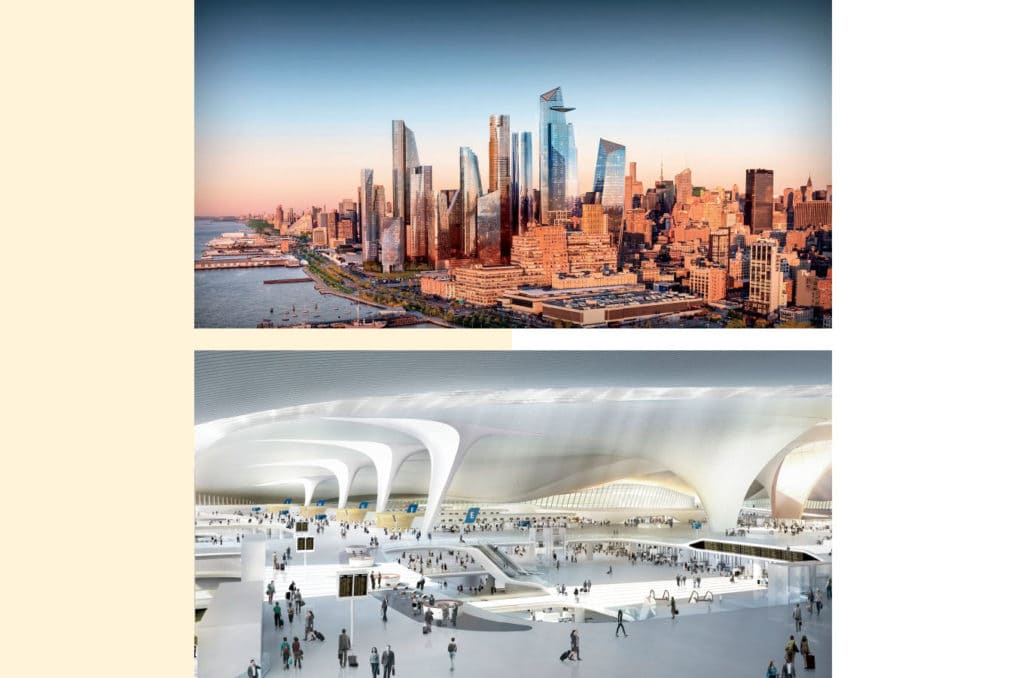

APEX Insight: As airports become more than just transit hubs, they’re turning into microcosms that emulate smart cities like Hudson Yards in Manhattan – a mixed-used development that will have its own microgrid and system of sensors for monitoring its environment. What do future airports have to learn from its hyperconnected communications network?

Welcome to Hudson Yards, a mixed-use development on the West Side of Manhattan. Like many New York City neighborhoods, this one has residences, offices, shops, restaurants, bars and public spaces. And being in a part of the city that sees a frequent stream of out-of-towners (Penn Station) and international tourists (High Line), there’s even a 16-story climbable monument, which could rival the Statue of Liberty as an NYC icon on Instagram.

What makes Hudson Yards a neighborhood to watch is that it’s a testing bed for future smart cities. The 18-million-square-foot site will run on a microgrid powered by one cogeneration plant and its own system of sensors to monitor its air, temperature, traffic, pedestrian flow and environment. Big data will also be harnessed to innovate, optimize, enhance and personalize the Hudson Yards experience for residents, employees and visitors. It’s no wonder why Intersection, the group of smart-city consultants who worked on the development and are now based out of the 26th floor of 10 Hudson Yards, sees potential for such a prototype to flourish in airports – another microcosm where sensors and cameras are used in abundance for security, baggage tracking, queue monitoring and air traffic surveillance.

“An airport should be one of the most seamless experiences in modern life.” – Max Oglesbee, Intersection

“If you think about it, an airport should be one of the most integrated and seamless experiences in modern life,” says Max Oglesbee, head of Client Strategy, Intersection. From a logistics perspective, the who, what, where and when of any trip are determined the moment someone books a flight. Given the airport’s role as the facilitator for the traveler and the airline (it has the itinerary of both parties), it should be able to choreograph their actions for maximum efficiency (delays and traffic factored in, of course). “With all of that intelligence, it should be a seamless experience where all the frictions are taken away,” Oglesbee says.

However, most airports dedicate one piece of technology per service needed, Oglesbee notes. Air traffic, CCTV video security, private and land mobile radio (PMR/LMR) and public Wi-Fi are each managed by a separate department. “This disparate network architecture discourages collaboration and information sharing among departments, which is crucial to attaining seamless operations and optimal efficiency,” telecommunications company Alcatel-Lucent notes in its white paper Re-imagining the Airport Network for 2020 and Beyond.

Take, for example, the reporting of security wait times at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution observed multiple manual methods: one where an airport worker identifies a random traveler in line and records how long it takes for that person to get to the front; another where a TSA agent hands a laminated card to the person at the end of a line and times how long it takes for that person to travel to the front; and another where wait time information is crowdsourced and reported via an app. But the results from these methods don’t always match, so the TSA continues to advise travelers to arrive at the airport two hours ahead for domestic flights, and three for international flights. “Most of the time, these systems are broken and fractal, inefficient, not only from a technology standpoint, but a user standpoint as well,” Oglesbee says. “It’s a complete waste of precious natural resources to deploy redundant systems on top of one another.”

A Digital Master Plan

During the development of Hudson Yards, Intersection held a town hall meeting to audit the many ways tenants might use the space. What it came up with was a digital master plan that listed all the infrastructure and technology that would be required to keep the neighborhood running. Everything from elevators to building security to ticketing systems was considered. In the end, Intersection counted many different systems, which were narrowed down to a handful of features that would be presented in various services and interfaces.

One example is 555TEN, a luxury apartment building near Hudson Yards that created an app enabling residents to access building services on their mobile devices – everything from receiving delivery notifications to booking a Pilates class to arranging a dog walk. The app is seeing high engagement: According to the New York Times, 93 percent of rent is paid through the app. Similar resident apps make tasks such as reserving a common area for a party or calling the building manager about a leak seamless. There’s even opportunities for local businesses to push promotions through the app. For residents, this layer of digital interaction on top of the physical experience is a cool tech perk. It’s also convenient – and convenience is a huge asset when you’re continually on the go.

To describe the type of user being targeted by the app, here’s a picture of a thirtysomething New Yorker on her way to the airport to meet a client in San Francisco: She’s checked in online with her airline already; her rideshare is about to pick her up any minute now. Once she’s in the car, she receives a notification that her flight will be delayed by 25 minutes. She decides to have a meal before boarding her flight and realizes she forgot to pack her noise-canceling earplugs. So she orders a caprese sandwich from an airport eatery and a set of noise-canceling earplugs from the electronics booth. Both will be delivered to her at the boarding gate.

“Modernizing [airport] communications network infrastructure is a critical step.” – Richard van Wijk, Nokia

“Trip planning for this person is about friction avoidance – not necessarily the fastest travel time,” Oglesbee explains. “Airports need to keep up with this next-generation of travelers who are thinking differently, who don’t have an allegiance to an airline. It’s about convenience, 100 percent.”

In other words, airports need to get smart – but not just dress the part. “Modernizing [airport] communications network infrastructure is a critical step,” writes Richard van Wijk, head of Aviation Practice, Nokia, a telecommunications consultant who oversaw the first LTE air-to-ground network for aviation in Europe, on SmartCitiesWorld, a website about smart city infrastructure. “The reasons are clear: Smart airports, smart cities, smart anything depend on data, and communications networks are the means for transporting and analyzing that data.”

The Changing Role of the Airport

Tomorrow’s airports – megahubs like Istanbul New Airport, Dubai World Central and Beijing Daxing International – have each been designed to accommodate upward of 150 million travelers a year. They’ll be equipped with automated check-in, bag-drop kiosks, biometric scanners and robots; they’ll feature shops, restaurants, bars and public spaces. Comarch, a global IT business solutions provider, calls this next-generation facility “airport 3.0.”

“The airports of the future will fully exploit the power of new technologies, including sensors, processors, mobile apps, gamification and behavioral analytics,” writes Vincenzo Sinibaldi, a former business development manager at Comarch Italy, on CityMetric, a website about urbanism. “The key is broad integration process among airlines, retailers, restaurants, cafés and parking facilities. In this model, airports can cross-sell and upsell to passengers.”

As airports expand their services, they’ll become better connected, too: Airport technologies will communicate with one another, breaking the “one service, one technology” relationship; beacons and GPS will create a more dynamic airport that’s responsive to travelers’ needs. And with these improvements, the airport is increasingly resembling the smart city. “Airports are like cities in microcosm, and they face many of the same challenges as the cities they serve,” van Wijk writes.

The first airports laid down the lanes for aircraft to take off and land. They had limited infrastructure but were sound. As airports evolve from big buildings on the outskirts of cities where flyers meet their airplanes to vibrant venues accessible from the city, travelers might see airports differently, too. Van Wijk further observes: “Commercial aviation is a very competitive business, and the airports that offer the most attractive facilities and amenities – along with operational excellence – tend to win out in the competition for routes and travelers.”

“Smart City, Smart Airport,” was originally published in the 8.1 February/March issue of APEX Experience magazine.