How has the airline industry recovered from mass disruptions in the past?

The coronavirus crisis came without notice. On January 9, Chinese officials announced the outbreak, with 44 confirmed cases and counting. The first major travel restriction came into effect in China two weeks later. On January 23, 15,072 flights carried passengers to the country in time for Lunar New Year, the world’s busiest travel rush, as cases climbed past 570 and a total shutdown of Wuhan, the center of the outbreak, was imposed. By February 13, daily flights had dropped to around 2,000 as more lockdowns were enforced and international airlines canceled trips to mainland China. On flights that did operate, magazines, pillows, hot meals and trolley service gradually disappeared.

By the time Wuhan’s 76-day lockdown was lifted on April 7, China experienced an air traffic disruption at least 15 times greater than the two-day closure of US airspace during 9/11. Worldwide, there were just 32,221 passenger jets left in the sky. Global coronavirus cases soared above two million the following week, and the airline industry as a whole was on pace to shoulder the adjusted economic impact of more than 30 SARS outbreaks by the end of the year. Economists projected the overall financial shock of COVID-19 would be three times greater than the steepest downturn of the 2008 global financial crisis.

“We have never shuttered the industry on this scale before. Consequently, we have no experience in starting it up.”

“We have never shuttered the industry on this scale before,” said Alexandre de Juniac, director general and CEO of the International Air Transport Association (IATA), during an April briefing. “Consequently, we have no experience in starting it up.” There’s no single past event that provides a roadmap for recovery from this pandemic. But a combined understanding of lessons learned after 9/11, SARS and other shock events will help chart a way forward.

THE WAY BACK

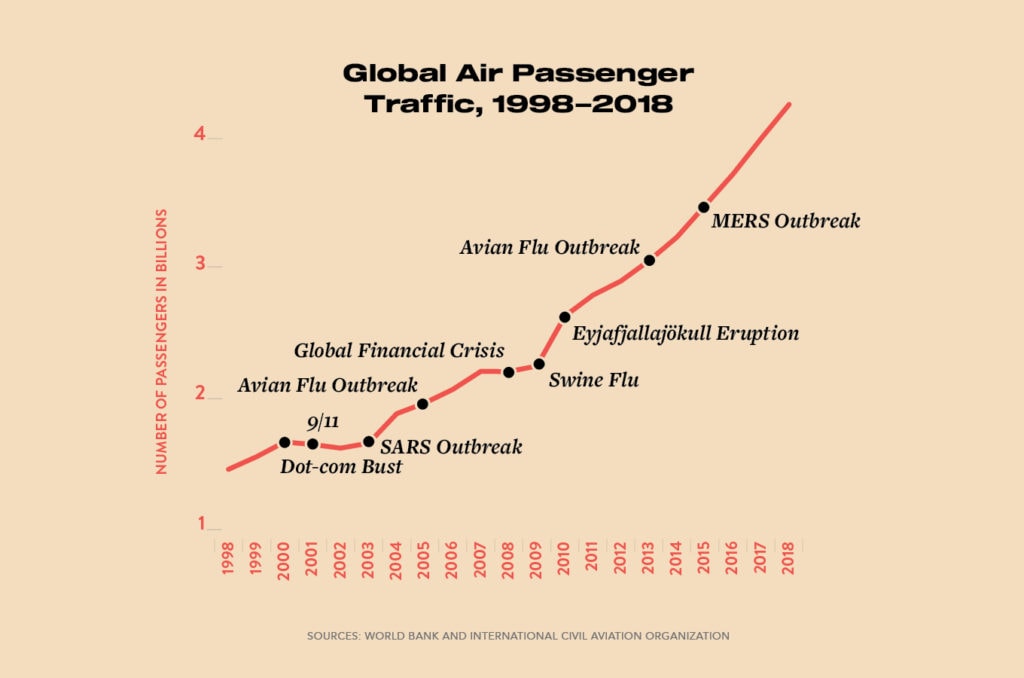

Every few years or so the airline industry gets rattled by a “black swan” event or economic downswing. After the Gulf War and the recession in the 1990s came the dot-com bust. That was followed by 9/11 and then mid-upturn, the SARS outbreak jolted East Asia and Canada between November 2002 and July 2003. A couple years later, the H5N1 avian influenza swept through Southeast Asia. The years following the 2008 global financial crisis were particularly turbulent, with the H1N1 swine flu pandemic in North America, and the eruption of Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano bringing European airspace to a standstill. The avian flu returned in 2013, then came Ebola, MERS and Zika.

Despite these downturns, world airline traffic has shown stable long-term growth since the 1970s. According to a 2015 report published by IATA called Global Air Passenger Markets: Riding Out Periods of Turbulence, it generally takes at least five years for the industry to recover after a short-term upheaval. “Approximately 72 percent of the impact of the initial shock persists one year after the event,” write co-authors David Oxley and Chaitan Jain. “Two years on, the effect of the shock on global air traffic is down to just over half of the initial effect, while after five years the effect is just under one-fifth of the initial impact.” When travel demand drops, the typical airline playbook reads as follows: decrease capacity, increase load factor, lower fares.

It took about six years for airlines to recover capacity after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, which before the COVID-19 crisis, caused the steepest historic decline in air traffic. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, travel demand in the US fell by more than 30 percent. The slump was met with significant capacity reduction and the loss of more than 62,000 airline jobs – 11 percent of the US industry’s employment at the time. Legacy carriers shifted some capacity to international markets and slashed airfares to compete with low-cost carriers that closed in on short-haul networks and benefited from deeply reduced aircraft prices. (In January 2002, Ryanair scooped up 100 Boeing 737-800s at a 53 percent discount.)

The COVID-19 crisis cuts much deeper. By April, more than 140 airlines slashed capacity down to 10 percent or less. Both Etihad Airways CEO Tony Douglas and IAG Group’s outgoing chief Willie Walsh have said they don’t expect to see meaningful demand return before July. Long-haul travel will be hit hardest, since domestic travel restrictions will relax before international bans are lifted. “For airlines, revenues are more dependent on passenger kilometers flown,” explained IATA’s chief economist Brian Pearce during the association’s April briefing. “Domestic [flying] represents one-third of passenger revenue kilometers, so obviously the slower opening of international borders is more problematic for the airline industry.”

The shutdown has also accelerated aircraft retirements, hastening the end of the jumbo jet era. Lufthansa plans to leave 32 aircraft permanently grounded, retiring six Airbus A380s, seven long-haul A340-600s and five Boeing 747-400s ahead of schedule. Germanwings, which operated under the low-cost Eurowings brand with 33 aircraft, will cease operations. And Austrian Airlines plans to downsize its fleet from 80 to 60 aircraft by 2022: “The entire airline industry is pessimistic,” executive board member Andreas Otto commented. “We have to assume that we will reach the ‘pre-corona level’ again in 2023 at the earliest.”

Load factors, meanwhile, could stay low if airlines adopt distancing measures such as keeping middle seats empty, as Delta Air Lines, Southwest Airlines and easyJet have offered. But carried out in the long term, a complex balancing act ensues. Lower-occupancy flights eventually require higher ticket prices – up to 54 percent above average in North America – while low demand and financial insecurity caused by a recession necessitate lower fares.

THE WAY FORWARD

Regaining revenue hinges on convincing travelers it’s safe to fly again. “And we don’t want to repeat the mistakes made after 9/11 when many new processes were imposed in an uncoordinated way,” said de Juniac. “We ended up with a mess of measures piled on top of measures. And nearly 20 years later we are still trying to sort it out.”

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, businesses froze non-essential travel and interstate traffic went up as Americans chose to drive instead of fly. To restore safety and confidence, the Transportation Security Administration went on a spending and hiring spree, adding some 40,000 border patrol agents, and electronic bag screening machines to airports. Travelers were asked to arrive on average two hours before takeoff, remove shoes while agents rummaged through their carry-ons and trust that checked bags would make it through labyrinthine screening belts.

“When people feel confident… that’s when the recovery will take shape.” – Ed Bastian, Delta Air Lines

Heightened security assured travelers, but the added hassle became its own deterrent, contributing to further decline in demand. Studies estimate this cost the industry an additional $1.1 billion in lost revenue, hitting the short-haul market hardest. While the economy bounced back, the inconvenience posed by security prolonged recovery for the travel industry. It took some five years for average airfares to return to pre-9/11 levels. While the Air Transportation Safety and System Stabilization Act (2001) provided $5 billion in compensation and $10 billion in loan guarantees, it took five years for US airlines to get out of the red, according to data from the US Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

Most economists agree that the industry’s recovery from the coronavirus pandemic will be U-shaped. Risk perception, and how it is addressed, will play a decisive role in determining just how wide and inclined that U will be. “Demand will be there when it’s safe to travel,” said Delta’s chief executive officer, Ed Bastian, on the airline’s first quarter earnings call this year. “When people feel confident… that’s when the recovery will take shape.” Several preliminary studies, including social media analysis by Fethr, have shown that safety and sanitation will be key priorities.

“At the end of the SARS crisis, temperature screening was a key factor in returning the sector to normal,” said de Juniac. “We need to find the equivalent process to take us to when a COVID-19 vaccine is available.” Measures will need to be authoritative and persuasive, while not too prohibitive or invasive as to pinch rebounding short-haul markets, where transportation alternatives are readily available.

International travelers have other risks to contend with, such as sudden travel bans and restrictions. “I fully understand the hesitation many people feel at the moment when deciding whether to book a flight or not,” said KLM’s chief executive Pieter Elbers in a letter to customers. According to IATA, 86 percent of travelers are concerned about being quarantined and 69 percent will avoid traveling altogether if a 14-day quarantine is required. To mitigate these risks, flexible rebooking policies could become a long-term expectation. Based on 2018 US airline reservation change fee revenues, that amounts to a $2.7-billion bid for leniency to stem reservation hesitancy.

As revealed by the impact of the SARS epidemic, which resulted in some 8,000 cases worldwide, predominantly in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and Canada, advisories and false starts can cause fear to linger. Rapid spread of the virus via international travel prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to issue its first SARS-related travel advisory on March 15, 2003. When Toronto was added to its list on April 23, the knock-on effect was immediate: At least 11 countries followed suit, recommending their citizens stay away. The advisory was lifted six days later, but non-US travel to all of Canada still dropped by 33 percent the next month. News of a second wave in late May wrought the most long-term damage. It took a full year, including $128 million dollars from the Ontario provincial government spent on marketing campaigns and a “SARS-a-palooza” concert before tourists returned to the city in pre-outbreak numbers.

Consumer confidence may be the biggest hurdle for the industry. According to a recent survey by IATA, 69 percent of travelers say they will need to feel more financially secure before they’re ready to fly again. Meanwhile, 60 percent say they would travel within one to two months of the pandemic being contained, and some 40 percent plan to wait six months or longer.

For airlines, the more immediate challenge is to stay solvent. Airlines were in good fiscal shape when the crisis began, but IATA expects them to burn through $61 billion in cash reserves by the end of June and add $120 billion to the industry’s global debt, totaling to $550 billion by year-end. Solutions airlines used after the 2008 global financial crisis, such as consolidation, higher densities and eventually ancillary fees, aren’t as readily accessible now as they were then. But other revenue ideas have emerged in their place, such as carrying cargo in the cabin.

While many airlines, including Delta, Southwest and Singapore Airlines, have raised considerable capital, Flybe has shuttered, and Virgin Australia and Air Mauritius have entered voluntary administration. Government aid, voluntary pay cuts and leave options have helped to abate some job losses, but rising furlough figures underscore the need for further financial support, say APEX and IATA.

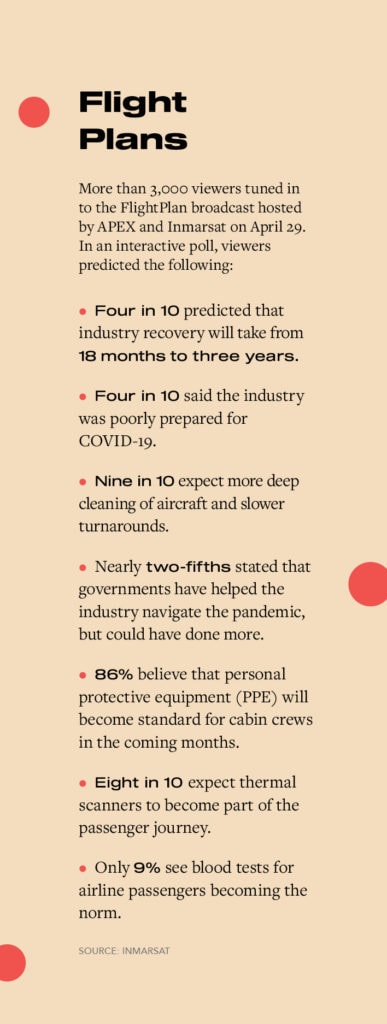

Some pages of the airline crisis management playbook are yet to be written. Fortunately, it’s a challenge many are rising to meet. The COVID-19 pandemic may have “no parallel to draw upon in recent memory,” said Nick Careen, senior vice-president of Airport Passenger Cargo and Security at IATA, during FlightPlan, a global broadcast hosted by APEX and Inmarsat. But “the airline industry has illustrated time and time again that if there’s any industry in the world that knows how to deal with a crisis, it’s this one.”

“Aftershocks” was originally published in the 10.3 June/July issue of APEX Experience magazine.