The passenger experience was always changing, but an era-defining pandemic has its way of speeding things along.

Elliot Kreitenberg and his father, an orthopedic surgeon and inventor, started out by disinfecting volleyballs. It was 2012, and they had heard that the US Women’s National Volleyball team had been instructed not to shake hands with their opponents after Olympic matches to prevent the flu from spreading. But what about the ball they had all been touching? Wasn’t it, too, a carrier of contagion?

After a series of tests confirming their suspicions, they got to work on a germicidal ultraviolet-C solution. With the younger Kreitenberg attending business school on the East Coast and his parents out in Southern California, air travel had become a fixture of their lives, leading the father-son dyad to also wonder if the UVC radiation technology they had devised for sporting goods might also be applied to aircraft cabins. After combing through research on the correlation between air travel and the spread of infectious disease, the pair dreamt up GermFalcon, a trolley with arms extending outward to limn the cabin with germ-zapping light at a rate of 30 rows per minute.

After the Ebola epidemic erupted in West Africa in 2014, Virgin America gave the Kreitenbergs access to its airplanes to use as testbeds for their work. However, when news of the carrier’s acquisition by Alaska Airlines broke, that relationship was severed, and so was GermFalcon’s direct link to the industry. “It was kind of a gut punch to us. We were at it for some time, trying to pitch the product to airlines for risk mitigation, as well as an emergency preparedness tool, but there wasn’t any other interest,” says Kreitenberg, who is co-founder and president of the company. In 2018, they decided to pivot from aviation to healthcare and built the UVHammer, a modification of the original unit, for use in hospital operating rooms.

Ironically, the UVHammer has, in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, circuitously made its way into airports, such as Seattle’s Paine Field, where it is now being operated regularly. “We’ve gone from basically zero aviation customers eager to work with us to over 50 that are dying to get their hands on units yesterday,” Kreitenberg says. The company is ramping up production to satisfy the deluge in demand from dozens of ground-based subcontractors, and airlines in Asia, the Middle East, Europe and North America. “We don’t think our invention is any more genius now than it was six years ago. Unfortunately, it just took an infectious disease outbreak for the demand to materialize.”

A few months back, no one could have predicted we’d be where we are today: aircraft idle, airports desolate and a timeline abruptly splintered in two, pre-and post-pandemic. Flight traffic numbers pummeled by the pandemic reveal the unprecedented nature of the crisis at hand, as does the industry’s speedy adoption of evermore stringent sanitization and hygiene measures. But when it comes to the airline passenger experience of the future, we may come to see more evolution, than revolution: a farrago of old ideas finding new audiences, of pre-existing trends and technologies getting fast-tracked to implementation and a reckoning of practices and processes that was perhaps already overdue.

There were others, like Kreitenberg, who before the current calamity had observed reticence among airlines when it came to sanitization. Over the years, numerous germ-busting concepts have surfaced in the media, including self-sanitizing lavatories from Boeing and antimicrobial coatings from Recaro, Lantal, Sekisui Kydex and others. Yet, it’s been rare to see an airline take on the mantle of employing them – or at least making noise about it. Speaking at a recent RedCabin webinar, Ronn Cort, president and COO at Sekisui Kydex, shared: “We’ve had materials that are antimicrobial for aircraft going back to 2007, but it wasn’t the priority. If we would bring it up, it was like ‘Don’t talk about that.’ It was not the subject that people wanted to lean into.”

“Unfortunately, it took an infectious disease outbreak for the demand to materialize.” – Elliot Kreitenberg, GermFalcon

As global air travel soared without the immediate threat of infectious disease, maintaining efficiency and low cost had been the priority for airlines, so much so that even the time dedicated to routine cleanings was being squeezed. (Southwest Airlines, for example, once extolled a 10-minute turnaround, during which it unloaded, tidied and boarded its aircraft. Doing so, allowed the airline to maintain low fares for passengers.) Speaking of the status quo, Devin Liddell, principal futurist at design consultancy Teague, says, “In the conflict between turn time and cleanliness, airlines have erred on the side of turn time, but meaningfully cleaning the cabin isn’t a ‘nice to have’ anymore.”

APEX board member and Japan Airlines VP Global Marketing Akira Mitsumasu agrees, saying: “There are a couple very hard trade-off decisions that affect aircraft utilization and fleet planning, but the pandemic has brought about an increased awareness of cleanliness and with that various perceptions as to which airlines or airports are clean. Cleanliness will emerge as an important criterion when choosing an airline.” According to the social listening experts at Fethr, a subsidiary of Black Swan Data, there has been a rapid upswing in concerns on social media about the presence of pathogens on board – a 996 percent growth between March and May, as observed across the company’s dataset of 900 million naturally occuring conversations.

And just like that the race to the cleanest has begun, with heightened measures announced, literally, every single day by airlines and airports. Delta Air Lines was the first to turn its enhanced cleaning procedures, which now include disinfecting every flight in its network using electrostatic sprayers, into a brand differentiator, with the introduction of Delta Clean. Southwest, Air Canada, United Airlines and others have since debuted their own branded versions. Meanwhile, AirAsia and Philippine Airlines have each garnered attention with photos of crewmembers donning head-to-toe protective gear, and videos of self-cleaning robots at Pittsburgh International, Incheon and Singapore Changi airports are also making the rounds.

The biggest impediment to restoring passenger traffic, however, isn’t the virus – experts say the chance of in-flight transmission is between one in ten thousand and one in a million, with use of face masks reducing that by tenfold – but the perceptions of those yet to be inured to the current state of things. “The main challenge facing airlines today is the same one we faced after September 11: Our customers are scared,” says Max Hirsh, research professor at the University of Hong Kong and managing director and co-founder of the Airport City Academy. “Back in 2001, they worried about terrorists hijacking their plane. Today, they’re afraid that flying could expose them to disease.”

“Cleanliness will emerge as an important criterion when choosing an airline.” €” Akira Mitsumasu, Japan Airlines

To battle these perceptions, the conspicuousness of sanitization measures is as crucial as their implementation, especially given the microscopic nature of the threat in question. “Passengers have appreciated being able to watch videos about the initiatives over just hearing about them. This is particularly the case for the less visible steps taken, for example, around air filtration, which has seen a 390 percent growth in volume and 51 percent growth in positive sentiment between March and May,” Will Cooper, head of Insights, Black Swan Data, says. “However, airlines and airports will also need to earn positive engagement through positive experiences that passengers will share online as and when they travel.”

In addition to the swell in newly formed coronavirus-related fears, airlines are in the unfortunate situation of having to address a laundry list of pre-existing grievances. Cooper highlights cabin hygiene, the presence of pathogens on board and disinfection as trouble areas that preceded the pandemic. “These concerns were pre-existing and were growing over the course of 2019 – albeit at a slower rate,” he says. During the FTE APEX Post-COVID-19 Airports webinar last month, Jan Richards, head of Insights and Planning at Dublin Airport, agreed that many of the trends that will be important moving forward already mattered to passengers. “Cleanliness was already the number one thing that drove satisfaction in airports,” she added.

In certain cases, concern is more warranted than in others. Take air quality, as an example. Experts agree that the use of high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters in most aircraft renders the air in cabins better than that in many other spaces, including in office buildings and hotels, and even on par with that in hospital isolation units. Yet, the notion that the air quality in planes is infinitely worse persists. “In the current climate of active disinformation, the ability to lead through communications will separate one sector from another in this recovery,” Liddell advises. “Airlines will need to meet misinformation and even disinformation head-on through communications anchored by metrics and best practices.” (In this case, 99.97 is the key metric, representing the percentage of airborne particles captured by HEPA filters.)

No matter how scrupulous airlines may be in keeping contagions at bay and communicating their efforts, they cannot control the fact that proximity to other people, especially after months of sheltering in place, spells danger to travelers. “Surveys on the ground are already showing that the majority of the population is concerned about leaving the house, let alone boarding a plane. You can very easily imagine a passenger wanting to remain in a cocoon-like state for the entirety of the journey, fearful of who or what they might come into contact with,” says Craig Foster, senior consultant and co-founder of Valour Consultancy.

Airlines and their partners have gotten resourceful in their efforts to impart a feeling of safety. Dividers, hoods and shields once floated for increased privacy in the cabin are now emerging as the possible salve to these fears, as have promises of social distancing on board, with Frontier Airlines, Japan Airlines, Delta, easyJet and others leaving middle seats temporarily empty. The measure gives passengers 18 inches or so of clearance between them and the next person – a far cry from the six feet considered responsible on the ground, and the up to 27 feet scientists say virus-bearing droplets can actually travel with the push of a sneeze. According to Cooper, “Airline talk of vacating middle seats was met with some positivity, but many passengers did not see this happening in practice in the long term. Others have questioned the impact this policy will have on the affordability of tickets.”

“The main challenge facing airlines today is the same one we faced after September 11: Our customers are scared.” €” Max Hirsh, University of Hong Kong

Indeed, the economics of air travel don’t exactly allow for long-term social distancing in flight (especially for low-cost carriers, as Ryanair CEO Michael O’Leary was quick to remark when the idea was first raised). IATA has gone on record saying it does not support leaving middle seats empty because of the associated cost increases, adding, “Mask-wearing by passengers and crew will reduce the already low risk.” After all, high-occupant density is intrinsic to the sustainability of airline operations, as it is for many other industries, including public transportation, restaurants and movie theaters.

The addition of privacy-enhancing accoutrements to seats has its own drawbacks, namely adding to the number of surfaces that will be touched and, therefore, must be cleaned. Foster agrees that minimizing opportunities for physical contact may be the way to go, with passengers likely already hesitant to touch even existing surfaces like touchscreens and point-of-sales terminals. “More likely, then, is the use of PEDs [personal electronic devices] as a remote control for the seatback screen. Interaction with one’s own device is fraught with less ‘danger’ and many of us already use our smartphones to control other smart devices at home.” Bluetooth and near-field communications could further limit the risk of interaction, as might eye-tracking and motion-sensing in the more distant future.

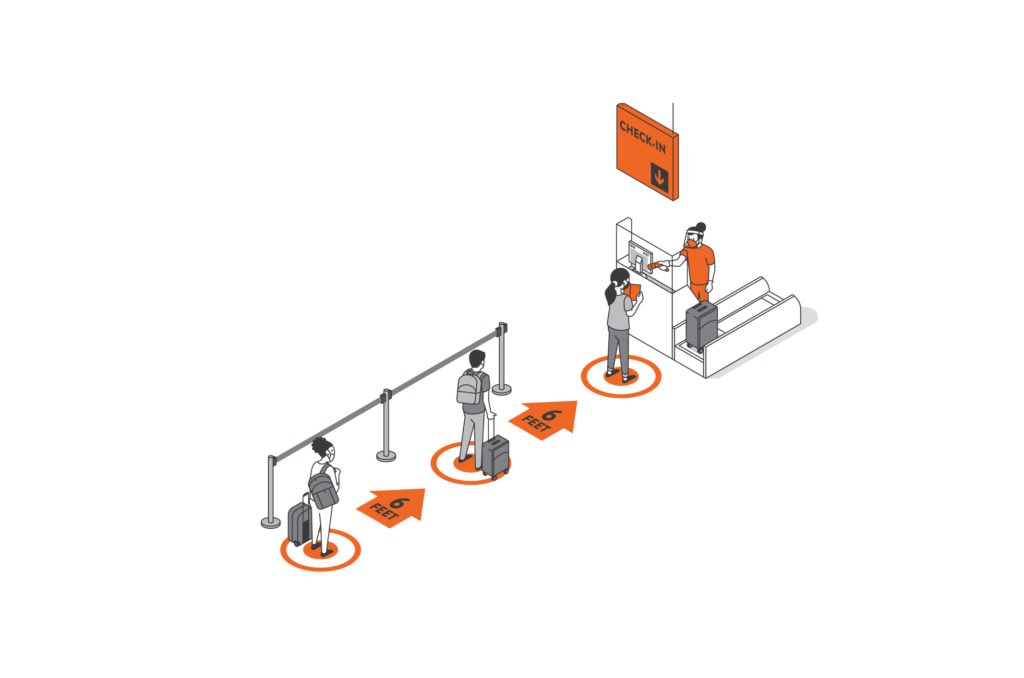

Of course, these efforts are futile if travelers remain tightly packed as they weave through sinuous queues at check-in, security and even as they grab a latte at Starbucks. Signage reminding travelers to wear gloves and don masks, floor markers encouraging distance, increased placement of sanitizer dispensers and plexiglass barriers are obvious first steps. Disinfection tunnels like that introduced at Hong Kong International Airport and AI-enabled computer vision that reduces crowding may follow. As for those automation and biometric technologies that airlines and airports have started to integrate with their systems over the past few years in the name of a more seamless experience? They may be just what is needed to reduce wait time, congestion and person-to-person interaction.

In the absence of widespread availability of a vaccine that can inoculate large swaths of the population and of universally accepted immunity passports, health screening may add an extra layer of logistics to the airport experience. Temperature checks via touchless thermometers and thermal scanners are being adopted widely (even though they fail to detect individuals who are asymptomatic), with more advanced systems like Elenium Automation’s kiosk being introduced by Etihad Airways to detect irregularities in vital signs at check-in, bag drop, security and immigration. At airports in Dubai and Hong Kong, rapid coronavirus blood testing has already been deployed.

The jump from enabler to inhibitor of disease would be a major coup for airlines and airports, Liddell says, but it requires a close examination of the fissures in existing structures as much as the heralding of new panaceas. “The pandemic is an emergency prompt to get going on things that we needed to get going on anyway. One of the things about social distancing that dovetails with the to-do lists that should already be in place is tackling the fact that we are already way over capacity. If we continue growing the way we were projected to – which we will – a lot of our infrastructure won’t actually support it.”

“You can very easily imagine a passenger wanting to remain in a cocoon-like state for the entirety of the journey, fearful of who or what they might come into contact with.” €” Craig Foster, Valour Consultancy

Liddell is right. There simply wasn’t enough floor space before and there certainly won’t be enough now to support a return to 2019 levels of capacity growth layered with 2020 social distancing measures. Decentralizing processes so that travelers can check in at a remote location, as dnata subsidiary Dubz has proposed, might be one element in the patchwork of solutions needed to ease the burden on travelers and the airport environment. Extending health screening procedures off-site may also help to avoid the undesirable scenario of turning away travelers who do not qualify for medical clearance after they’ve already made the trek out to the airport.

Top of the to-do list though, according to Liddell, should be an update to the boarding process, which has been broken for ages. “If you look at the core piece of technology at the gate, it’s about 100 years old: the loudspeaker, which remains the way in which we actually communicate to travelers upon boarding. It’s astonishing because not even my local deli operates via loudspeaker anymore.”

Unable to get their information otherwise, passengers crowd at the gate to ensure they won’t miss their flight and will be able to secure some coveted overhead bin space. It’s an issue Delta began to address pre-pandemic, with an update to its FlyDelta companion app, which sends passengers notifications for when their seat – not just their flight – is boarding. A fast-spreading coronavirus dictates that solutions like these, which allow travelers to percolate throughout the airport, perhaps engaged in discretionary spending, will continue to matter.

There is enormous pressure to “return to normalcy,” but pandemics have a way of leaving their mark. In the nineteenth century, cholera outbreaks gave way to modern sanitation systems and new zoning laws that curbed overcrowding. In the 1900s, the spread of tuberculosis reoriented the design of urban spaces to prioritize fresh air and sunlight. And though still too soon to tell where traces of coronavirus will endure, they most certainly will. Passengers, airlines and the communities they serve will not be spared.

One welcome change would be a reappraisal of the rules by which passengers relate to each other. “Right now, passengers don’t look at the person next to them at the gate or on board as a member of their community; they either don’t think about their well-being at all or look at them as a competitor for resources they want, like bin space,” Liddell says. “This is a prime example of airlines failing at leadership. They haven’t been communicating to passengers what they expect of them: a sense of collective responsibility.” Suddenly, under the high stakes of the current dire circumstances, passengers are in a position where they must depend on each other for their own health and safety, and airlines need to remind them of that.

There’s indication that this change is already underway. When JetBlue announced on April 27 that all passengers would be required to wear a face covering, the airline’s president and COO, Joanna Geraghty said, “Wearing a face covering isn’t about protecting yourself; it’s about protecting those around you. This is the new flying etiquette.” Meanwhile, Fethr’s social listening shows that KLM’s frequent flyers organically came together in the early days of the pandemic to fill the gap left by an overwhelmed customer service department. “Their passengers started relying on each other and a community emerged, with frequent flyers advocating for the brand and making recommendations based on their own experiences,” Cooper says. “KLM appears to have successfully built on that positive community spirit, with passengers now viewing the airline’s response to travel disruption more favorably in comparison to other airlines.”

“The pandemic is an emergency prompt to get going on things that we needed to get going on anyway.” €” Devin Liddell, Teague

On the industry-wide level, calls for collaboration are numerous. Associations like APEX and IATA have rallied support for coordination on applications for government aid and the implementation of health and safety measures, such as mandatory face coverings. Establishing globally binding health reporting standards and a mechanism for medical clearance will also require deep collaboration among governments, healthcare services, airports, airlines and related parties, Mitsumasu says. “Daunting as this may sound, it is possible today technology-wise,” he adds.

Will the industry suddenly operate in perfect unison? Of course not. There’s no idyllic new beginning in store because there’s also no hard break from the past. But that’s not all bad, especially for an industry whose prior investments in automation, privacy and wellness amply prefigure the strategies being taken today to stymie the spread of the virus. There’s also no going back to a time before we could understand the duty we have to each other. What will remain – and what have yet to be fully realized – are all the subtle, meandering steps forward.

“Where to From Here?” was originally published in the 10.3 June/July issue of APEX Experience magazine.