Aircraft Seat Design That Dives Beyond the Stats

Share

APEX Insight: Taking a cue from UX designers, creatives in the aircraft seating space, Acumen Design Associates, Factorydesign and tangerine, are looking ahead to the possibilities of real-time data.

“People don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” So said former CEO and co-founder of Apple, Steve Jobs, referring to the efficacy of focus groups in design, and echoing another famous quote commonly dredged up during debates on innovation: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” Henry Ford is purported to have said that one, although there’s some dispute there. Either way, the case for the lone visionary who overlooks the facts and feedback in search of something more profound is as old as it gets.

Designers have been mistakenly cast in a similarly prophetic light, says Martin Darbyshire, CEO of London-based design consultancy tangerine. “Everything we do in design is based around context,” he says. “That is the difference between art and design: Art essentially has unbounded context – apart from limitations like how much money is needed to create something. Meanwhile, what design is about, and should be about, is creating the best possible outcome for a given context.”

A Matter of Fact

Arriving at a successful design, Adam White, director and owner of Factorydesign, says, requires that fine balance between the empirical and the imaginative. “Some people view the world, and therefore design in the world, by thinking in very measured and definable strokes, while others rely on inspired, visionary jumps,” White says. “There’s a clash, but it is a very healthy one. What you need to do as someone running a design business is make sure you have all the bases covered.”

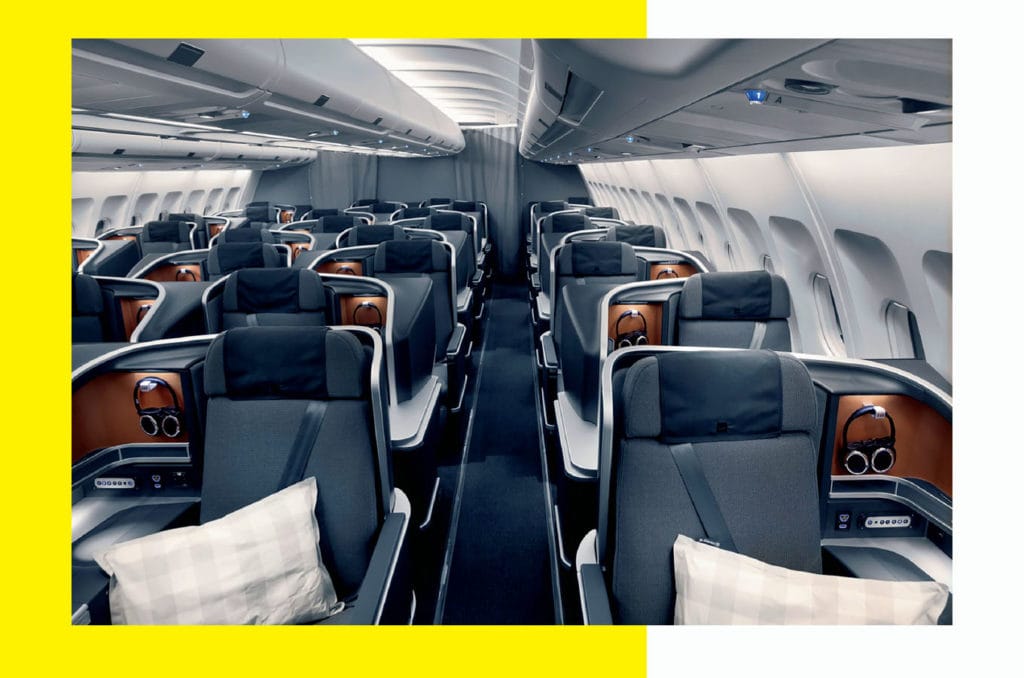

Nowhere do “measured and definable strokes” matter more than in the aircraft seating business. “You are trying to design a mechanical system which overcomes a 9g downward drop and stops every part of the skeleton from hitting the mechanics below. Whatever you do beyond that point is going to be incremental,” Darbyshire says. “It doesn’t matter how many people write ‘innovative,’ ‘the latest,’ ‘more this, more that’ on their adverts; the truth is that what most companies are actually talking about is very limited because of the restrictions imposed in a highly regulated industry.”

“When you introduce something that is empirical in nature, it acts like a salve for people who have decisions to make.” – Adam White, Factorydesign

Apart from ensuring that safety protocols are met, hard data has proven useful in laying bare the merits of one design over another to airline clients. As White puts it: “When you introduce something that is empirical in its nature, it acts like a salve for people who have decisions to make.” Hard data has certainly helped seating designers reassure clients in the boardroom, but its usefulness at the drafting table has some limits.

Concepts That Count

Focus groups, surveys and interviews can clue designers into which aesthetic details – color, material and finish, for example – will go over best with a certain community. Indeed, such market research has led to the many permutations of Thompson Aero Seating’s Vantage and Vantage XL seats, developed in partnership with Factorydesign, and adopted by the likes of Delta Air Lines, Scandinavian Airlines, Malaysia Airlines and others.

Barring smaller-scale customizations, current quantitative research falls short in providing aircraft seating designers with the insight needed to create something truly innovative, Darbyshire says. “We find that we learn an awful lot more as designers from observing people than from reading reports completed by market research agencies.” And this is true for most industries, he says, citing a project the firm is working on in the cosmetics sector. “One client presented a massive market research report for us to wade through. When we got to the end of it, I thought, ‘What am I actually learning here? What is this really doing to push the boundaries forward?'”

Sometimes market research is vapid (and that’s bad enough), but other times it’s just plain wrong, Darbyshire observes. In the year 2000, when British Airways (BA) presented tangerine with a brief requesting it to “find us the holy grail of airline travel sprinkled with a bit of pixie dust – and astound us along the way,” the agency responded with “Project Dusk,” a design for fully lie-flat beds in an unprecedented yin-yang formation. BA recruited a market research agency to present tangerine’s mock-up, as well as that from a competing agency, to some 100 customers.

Ten percent of people interviewed said they categorically would not fly facing backward.

“The recommendation from the agency was to not go ahead with our route, the yin-yang design, because 10 percent of the people interviewed said they categorically would not fly facing backward,” Darbyshire says. “Of course, that was very alarming. But the leader of the project said, ‘I want to check that out. We have to make sure that is actually correct.'”

And so some secondary research was conducted, including interviews with approximately 2,500 travelers in an airport lounge. This time the question – Would you fly facing backward? – was buried in the questionnaire, and the results varied widely. “Now only one percent said they categorically wouldn’t do it, and that changed BA’s mind about whether this was a big risk or a smaller one,” Darbyshire explains. “The way information is presented to people and the way questions are asked can lead to a dramatically different outcome.”

Ian Dryburgh, CEO and founder of Acumen Design Associates, agrees that quantitative research hasn’t always been the best barometer for success, pointing to his work on BA’s first-class cabin in the mid-1990s, which gave rise to the world’s first lie-flat seat. Although existing data suggested upping the number of seats in first class would increase revenue for the airline, the firm’s designers decided to follow their intuition, reducing the passenger count from 18 to 14 instead. “‘The Bed in the Sky,’ as it came to be known, won every design award going and, crucially for BA, led to a waiting list full of passengers wanting to fly the product,” Dryburgh says.

Living Proof

Current mechanisms for data collection and analysis in the aircraft interiors sector can yield clues as to what might or might not succeed, but fail to provide a clear picture of what will radically improve the passenger experience. That brings us back to Jobs and Ford, and to the reality that consumers may be unable to articulate what it is that they actually want. “Focus groups can provide insight into how passengers perceive certain elements of a design, but a design’s success is about more than what passengers say – it’s about what they do,” Dryburgh says.

“A design’s success is about more than what passengers say – it’s about what they do.” – Ian Dryburgh, Acumen

Predicting the future may forever be outside the realm of design – and human capability, for that matter – but the advent of on-demand processing of vast amounts of data may direct designers to the “why” of human behavior, without the information being diluted by recall bias. Real-time monitoring using beacons, sensors and other such technologies has already emerged in commercial aviation, with major airports around the world using it to better manage and understand traveler flow through security zones, airline lounges and retail environments.

This type of data, gathered from connected devices rather than people, is still in its infancy in the aircraft interiors sector. But introducing something as simple as low-cost sensors in the cabin could have major implications, Darbyshire says, including changing how airlines plan their meal service, logging how much passengers move in their seats and developing new ways to gauge their level of happiness.

“There is an intimacy between live data and the physicality of what people are actually doing.” – Martin Darbyshire, tangerine

Dryburgh says that closely monitoring how passengers interact with their material environment could help designers devise spaces that better reflect how humans actually behave in the air: “If we knew what proportion of time passengers were resting, working or out of their seat socializing, we could in theory develop an interior with designated zones for these activities,” he says. The firm imagines a space with a viewing deck that passengers could reserve, as well as areas for working, sleeping and eating, which they could freely enter and exit. “With a better understanding of how people interact with the cabin environment on a granular level, designers have the potential to create something truly revolutionary.”

Data collection that unlocks micro-insights about the lived, subconscious experience of space may just be the only way for airlines to move beyond incremental tweaks when it comes to aircraft interior design. As Darbyshire puts it: “There is an intimacy between live data and the physicality of what people are actually doing that simply cannot be replicated with any other research technique.”

“Beyond Measure,” was originally published in the 8.2 April/May issue of APEX Experience magazine.