APEX Insight: SpaceX announced this week that Japanese entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa has purchased room for himself and 6-8 artists on board SpaceX’s Big Falcon Rocket spacecraft. The group will be part of SpaceX’s first private lunar mission, which is expected to take place in 2023. APEX Media spoke with experts working at the seams of space and aviation to find out how plans for space tourism are bringing new ideas into rotation for airlines.

That curiosity in the cosmos is an inexorably human trait – or a “genetically encoded force,” as one Neil deGrasse Tyson put it – is being put to the test by Richard Branson, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and others looking to democratize space exploration. Once regarded a topic broached only by NASA and the likes of Douglas Adams and Arthur C. Clarke, outer space has now entered the realm of possibility for the traveling public, and with it a new idea of what the passenger experience could look like.

As billionaires busy themselves with the task of getting their first space tourists off the ground, airlines must still contend with the now thankless job of transporting large groups of people across the Earth as quickly, efficiently and economically as possible. But experts working at the seams of space and aviation say that looking to the stars could teach airlines a thing or two about travel on Earth, too.

LESSON ONE: Bring back the glamour.

Before the long queues and flight delays, air travel marked the apogee of adventure and allure. In the early 1900s, newspaper and magazine articles chronicling unprecedented aerial feats were circulated widely and air shows drawing international crowds became a major spectator sport. “The pioneers of the first flights were seen as glamorous – heroes even. And then flying was for the rich, an exclusive club. It evolved until it eventually lost its glamour,” says Paul Priestman, chairman of PriestmanGoode, a design consultancy that counts Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, World View Enterprises and a number of international airlines among its clients. Space tourism may someday meet the same fate, he says, but until then, airlines better watch and learn from entrants in the sector on how to channel some of that romance.

“The pioneers of the first flights were seen as glamorous – heroes even.” €” Paul Priestman, PriestmanGoode

One way, Priestman says, is for carriers to focus on the segment of the journey where some of that thrill still exists: the moment right after travelers’ book their flight. “It’s a really interesting psychological moment that brands need to mine because, often, the anticipation is better than the experience. You haven’t had all the problems at the airport or the bad experience at the hotel yet. It’s a utopian holiday in your mind when you press that button,” he observes. “Space travel can teach us about that anticipation, but it’s up to us to apply it to our world-based travel.”

LESSON TWO: But remember, nothing feels quite like home.

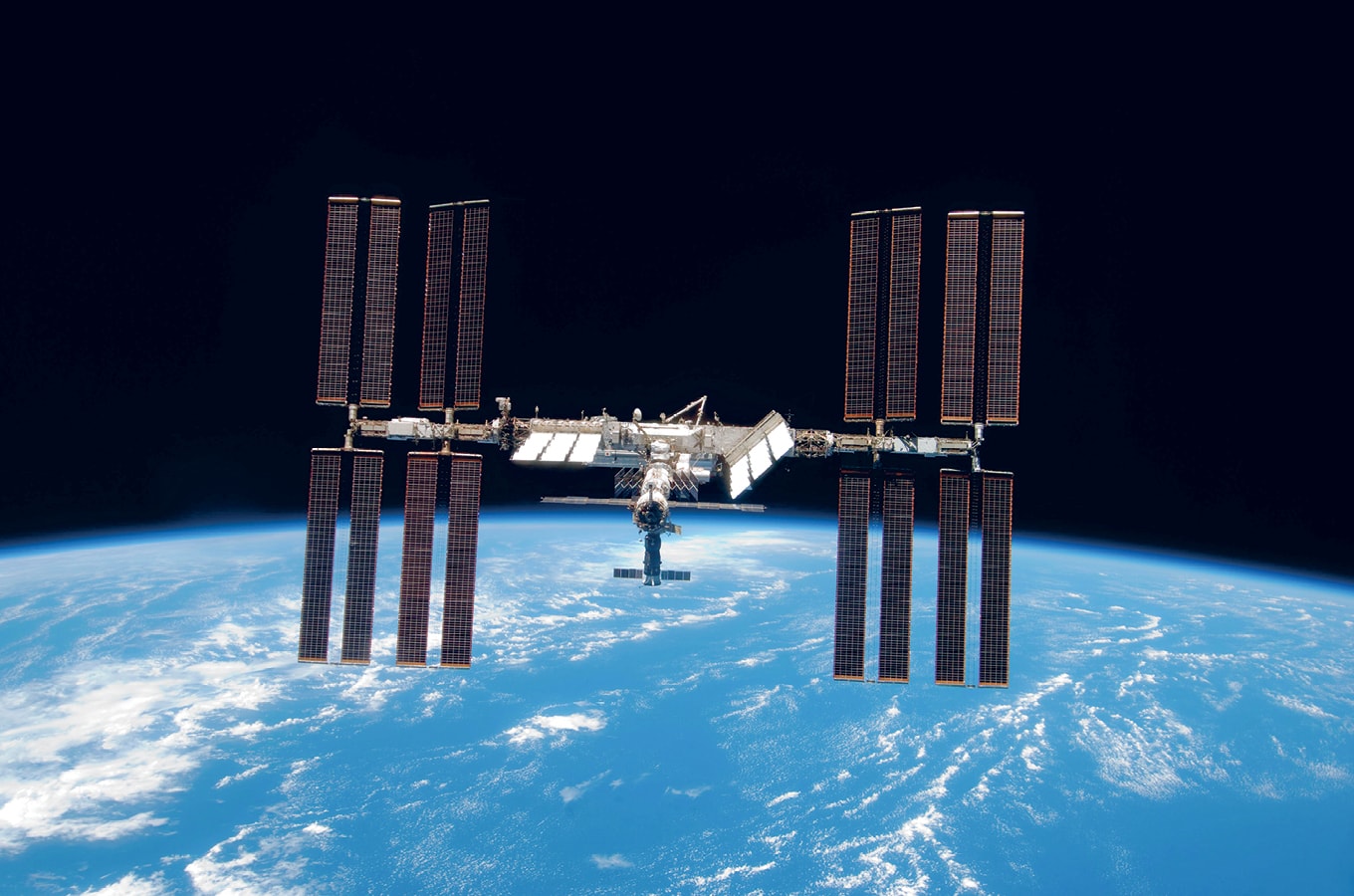

For all the newness that space travel conjures, those who’ve already been blasted into the cosmos emphasize the importance of feeling connected to what they’ve left behind. For European Space Agency astronaut Alexander Gerst, currently completing a six-month stint at the International Space Station (ISS) for the Horizons mission, that meant stocking up on some nostalgia-inducing dishes from Germany’s southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg, where Gerst is from, says Jörg Hofmann, director of Culinary Excellence at LSG Group. The airline catering firm ventured into the space sector for the first time when it was tasked with developing “bonus foods” (specific items chosen by crewmembers that are in addition to the standard space menu) for the astronaut. “One of the foods we created for Alexander was a traditional dish called kaese spaetzle. Gerst said, ‘I would love to have this on board with me because it reminds me of someone.'”

According to Hofmann, this level of personalization isn’t too far off for airlines, pointing to initiatives like LSG’s FlyYourVeda, which gives flyers the option of either an activating or relaxing meal. “Personalization is going to play a bigger and bigger role,” he says. “And in first class, where we are talking about just eight people, the same level of personalization that we see for astronauts should be possible.” In the meantime, Lufthansa business-class passengers flying long-haul from Germany this past summer were able to dine like an astronaut, sampling Gerst’s bonus food – albeit at some one million feet closer to Earth.

LESSON THREE: Reconsider the human factors.

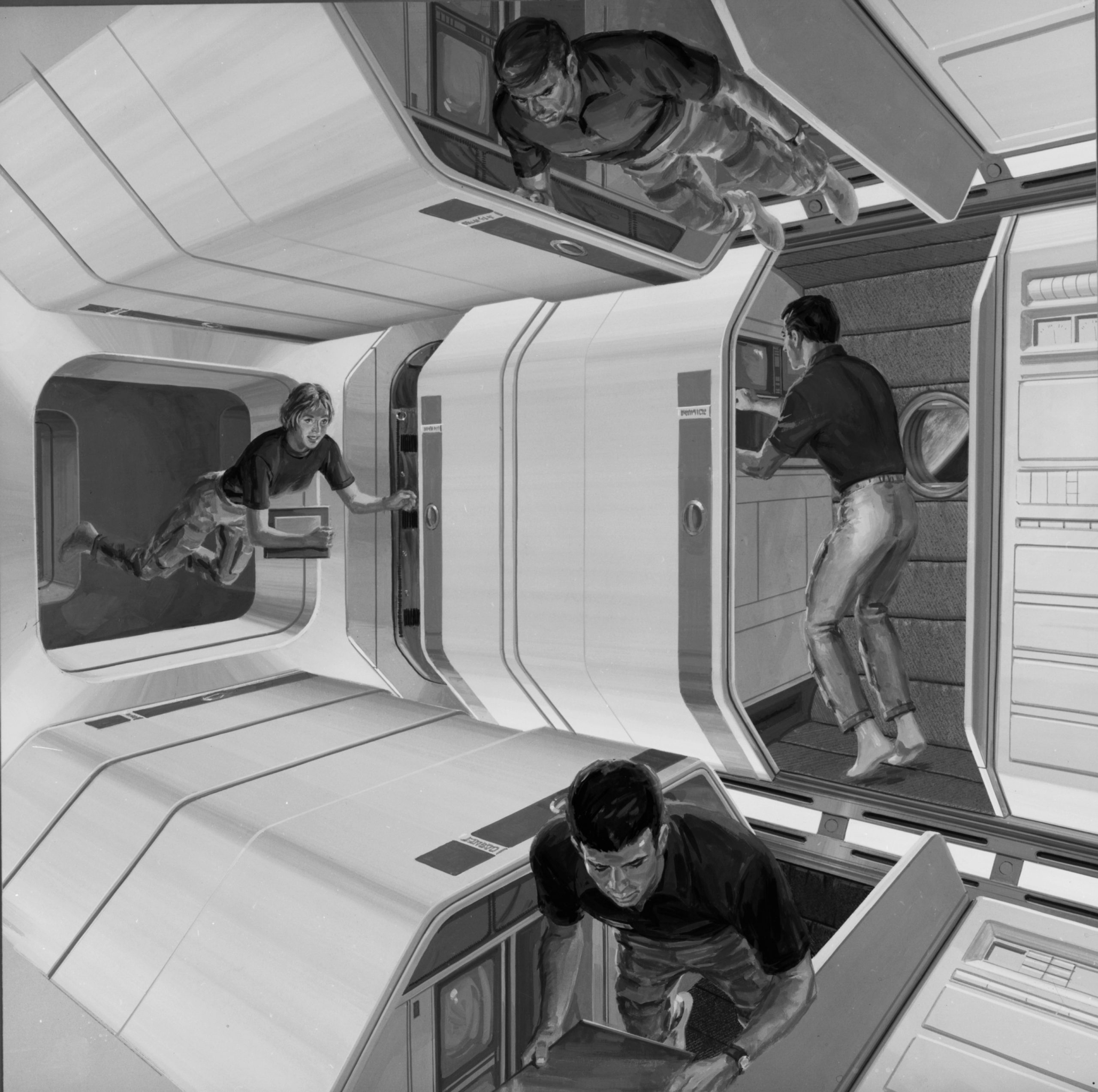

The study of human factors – how humans relate psychologically and physiologically to a given product or environment – has been mission critical to space science, prompted by the challenge of working in zero gravity. Not always so in aviation, says Rick Fraker, industrial designer and CEO of design consultancy Doodle Corps, who has worked on interior architectures in the aerospace sector for the past 30 years, citing flight deck requirements and flight crew needs as notable exceptions. “Commercial aircraft interior designers rarely integrate true human factors skill sets into baseline interior architectures. Too often, solid analysis is bypassed in favor of qualitative research techniques.”

Part of the solution lies in manufacturers rethinking human factors as an asset, rather than a hurdle: “A misconception human factors professionals too often deal with in large-scale production cycles is that their investigations slow what is considered ‘normal’ product development schedules,” he says. “As a fallout, most interior architectures are approved with only a little science to back them up.”

“Commercial aircraft interior designers rarely integrate true human factors skill sets into baseline interior architectures.” €” Rick Fraker, Doodle Corps

Carrie McEwan, senior human factors specialist at Teague, maintains that the issue with human factors research in aviation isn’t the frequency of its application, but instead the widespread belief that it isn’t already embraced by the industry. “We do extensive human factors research on every product we introduce into an airplane, including new cabin products and passenger experiences that will be flying in the near future, [but] it plays a more visible role in space right now because space travel is currently limited to those who are highly trained.”

Whichever the case, with space tourism soon within reach of the general public – and the whole world monitoring its development, there will likely be a renewed focus on the study of human factors, and, as a result, airline passengers stand to benefit.

LESSON FOUR: Variety is the spice of flight.

Sitting is the new smoking, Priestman says, as he discusses some of the drawbacks in airlines’ aspirations for record-breaking air times. On October 12, Singapore Airlines will operate its first flight with the freshly minted Airbus A350-900 Ultra Long-Range jet, ushering in the return of the world’s longest commercial flight, from Singapore to Newark, clocking in at just under 19 hours. “Obviously, it will be a bit better for people in business and first [class], but for people sitting in economy for 19 hours, the seats will need to be adapted,” he says.

Though airline passengers may never be able to somersault at will (as long as gravity is in the picture), something as small as being able to shift to the left or right in their seats – as opposed to just backward or forward with the recline mechanism – could help vary the experience, Priestman says. Making it easier for passengers to get up and wash their hands and brush their teeth would also be appreciated, he adds.

“I care about the flowers much more than I was expecting to, partly because I’ve been missing the beauty and fragility of living things.” €” Scott Kelly, Endurance: A Year in Space, a Lifetime of Discovery

As flights get longer, perhaps someday even reaching the 24-hour mark, airlines may have to consider different ways to accommodate passengers’ daily psychological needs. After all, even in the ISS, where residents witness a sunrise every 90 minutes, a 24-hour schedule composed of work time, sleep time and down time is observed. In his memoir, Endurance: A Year in Space, a Lifetime of Discovery, astronaut Scott Kelly, for example, writes about how being tasked with growing lettuce and zinnias on the ISS – to test the feasibility of fresh produce for future travelers to Mars – nourished a psychological need. “I care about the flowers much more than I was expecting to, partly because I’ve been missing the beauty and fragility of living things,” he writes.

LESSON FIVE: Proximity breeds camaraderie.

The main module on the Apollo spacecraft measured some 210 cubic feet. On the Soyuz rocket that brought Gerst and two other astronauts to the ISS in June, it was closer to 140. NASA’s latest craft designed for deep-space exploration, the Orion, can accommodate 316 cubic feet of habitable space – larger yes, but still about the size of a cramped office space, due to severe weight restrictions (the heavier the craft, the more thrust required of the rocket motor to propel the vehicle into space).

It won’t be much different for the next generation of people movers, says Christopher Pirie, senior director of Business Development at Teague, a design firm that began working in the space sector in the late 1980s when it collaborated with NASA and Boeing on the design of the Habitat Module for the ISS: “All materials and touchpoints need to earn their way into the vehicle; this becomes hyper-relevant when lifting tons of equipment and people into space.” Today, Teague is working with a number of unnamed clients “on every aspect of the space travel passenger experience,” Pirie says

But close proximity and prolonged confinement may be the very reasons astronauts report such high levels of camaraderie, Fraker says. “The same may soon be true for space tourists. Can airlines borrow this idea and apply it to their cabin designs?” he asks.

Operators of ultra-long-haul flights could harness the bonding power of physical proximity if they find a way to veer away from the current cabin configurations, Priestman says. “When you are in a smaller compartment, like a train carriage, you’re more likely to speak to people because you are a part of a small community. But when you are in a bigger space, like a 200-plus economy cabin, you are less likely to,” he explains.

With flight times getting longer, airlines are going to have to look at how to create shared, memorable experiences predicated on meaningful interactions, rather than isolation. “Because of the length of flight, putting on your eyeshades and getting to sleep won’t be enough. It’s going to have to be different psychologically,” Priestman adds.

LESSON SIX: Don’t conceal the journey.

Despite the exorbitant price tag attached, space tourism continues to fascinate because, thanks to the view – “the glory of the world below and the universe beyond,” as Pirie describes it – the journey is as captivating as the destination itself. And as such, he asks, “How does one create an environment that feels safe, secure and at home while celebrating the brave new world of space exploration?”

Priestman points to his firm’s work on the interior and exterior of World View’s Voyager balloon capsule with its immersive dual-pane glass windows, as one possible approach. “Airline passengers are going to want bigger windows, too. Airlines can achieve this digitally if they want, screening what cameras are seeing outside the aircraft or maybe with skylights down the center of the aircraft. But they are going to have to respond,” he says. “The idea of falling asleep and being able to look at the stars – that’ll help passengers enjoy the moment.

Pirie likewise suggests that instead of “looking for opportunities to distract passengers from the monotony and discomfort of long-haul travel via food service, entertainment and shopping,” airlines gain inspiration from the natural scenery beyond the window.

“How does one create an environment that feels safe, secure and at home while celebrating the brave new world of space exploration?” €” Christopher Pirie, Teague

Teague’s own efforts in bringing the outside in began with its work on the Boeing 787. “The size of the Dreamliner windows paired with advanced dynamic lighting, expansive architecture and material layering brought back the magic of flight, and offered every passenger a unique and deeply personal view of the world,” Pirie says. Teague has since brought that rationale to Emirates, which offers “vaulted ceilings and a starry night sky overhead,” tapping into that same sense of wonder, Pirie says.

But as the distance between Earth and the expanse beyond shrinks with the prospect of commercial space travel, the very meaning and feelings associated with nature may change. The moon’s surface, for example, is craterous and its lighting harsh, and combined with reduced depth perception, it’s anyone’s guess whether design inspired by the lunar environment will inspire awe, fear or a completely new feeling in between.

“Lessons From Space” was originally published in the 8.4 September/October issue of APEX Experience magazine.