Pledges to curb carbon have been made, investments in electrification are on the rise and viable alternative fuels are, at last, in the pipeline. But activists, scientists and even airline executives worry that efforts to decarbonize the commercial aviation industry remain at odds with some of its long-standing practices.

Until 2019, “Greta” was the name of an old Hollywood star, a contemporary indie writer-director with a feminist edge or maybe just that of a distant German relative. Now, the name is plastered on protest paraphernalia, entering the lexicon of world leaders and being invoked as more than just a proper noun – when placed before “effect,” it denotes the massive wave of response a 17-year-old Swedish climate change activist has elicited, from peers to politicians.

Some who once boasted about weekends spent city-hopping are now marching to the tune of Greta Thunberg, who famously sailed across the Atlantic on a two-week journey to attend a United Nations Climate Action Summit in New York to avoid the carbon emissions caused by flying. Her voyage drew attention to a new movement, dubbed flygskam (a Swedish neologism for “flight shaming”), aimed at rousing guilt among consumers for their aviation-related carbon

footprint, which accounts for about 2.5 percent of global emissions.

“The news stories tell it all: Air travel is now high on the agenda.” €” Scott Cohen, University of Surrey

Scott Cohen, professor of tourism and transport at the University of Surrey, has been studying attitudes toward commercial aviation over the past 10 years and says the public has undergone a seismic shift with Thunberg and the associated Extinction Rebellion (a non-violent climate change crusade). “The news stories tell it all: Air travel is now high on the agenda. Many of us have been looking at the environmental impact of aviation for a decade, but it was left out of the mainstream discussion until now.”

To be sure, airlines have been making sustainability gains for far longer than just a year. As IATA CEO Alexandre de Juniac explains in a press release, carbon emissions from the average airline passenger journey are about half of what they were in 1990, and, in 2008, the industry committed to capping net emissions at 2020 levels and halving them by 2050. APEX/IFSA CEO Dr. Joe Leader cites similar figures, adding that, “If every other industry had been as environmentally focused on reducing fuel utilization per person as aviation, then we likely would not have a global warming crisis today.”

“I quite like Extinction Rebellion and Greta Thunberg for having brought a real focus to the issue – a focus on the fact that we are not doing enough at the speed we should be.” – Sir Tim Clark, Emirates

These efforts, however, are eclipsed by the exponential growth in air travel, projected to double over the next 20 years and buoyed by the boom in low-cost carriers (LCCs) and surge in demand from emerging markets. Even airline executives like Sir Tim Clark can admit, “I quite like Extinction Rebellion and Greta Thunberg for having brought a real focus to the issue – a focus on the fact that we are not doing enough at the speed we should be. We really need this kind of thing to force us to make decisions.”

In Sweden, where flygskam was born, it has already served as a catalyst for change. The country’s airports saw a nine-percent drop in domestic flights, and its flag carrier a two-percent downturn in traffic compared to 2018. SAS has since taken steps to appeal to wary flyers, including eliminating its duty-free program, introducing biofuel purchasing to passengers and taking delivery of the more fuel-efficient next-generation Airbus A350. Pressures may be higher in Europe, but rippling media headlines, social media shares and climate marches show that carbon consciousness has spread, and perceptions of flying are changing in response. Many believe the industry must, too.

NARRATIVE SHIFTS

When KLM launched its “Fly Responsibly” campaign in June, with a video encouraging travelers to ask themselves if they could replace face-to-face meetings with videoconferencing and if they could take the train instead of the plane, confusion set in: Why would an airline ask travelers to stop doing that very thing on which its existence is predicated?

The airline at the time was celebrating its centenary but also plotting its next hundred years. “We owe it to the next generations to find solutions for the next century,” says KLM’s sustainability manager, Esmée van Veen. “We have only one planet, and when it comes to the future of sustainable aviation, the expectations are sky-high. No one wins in a world that loses.”

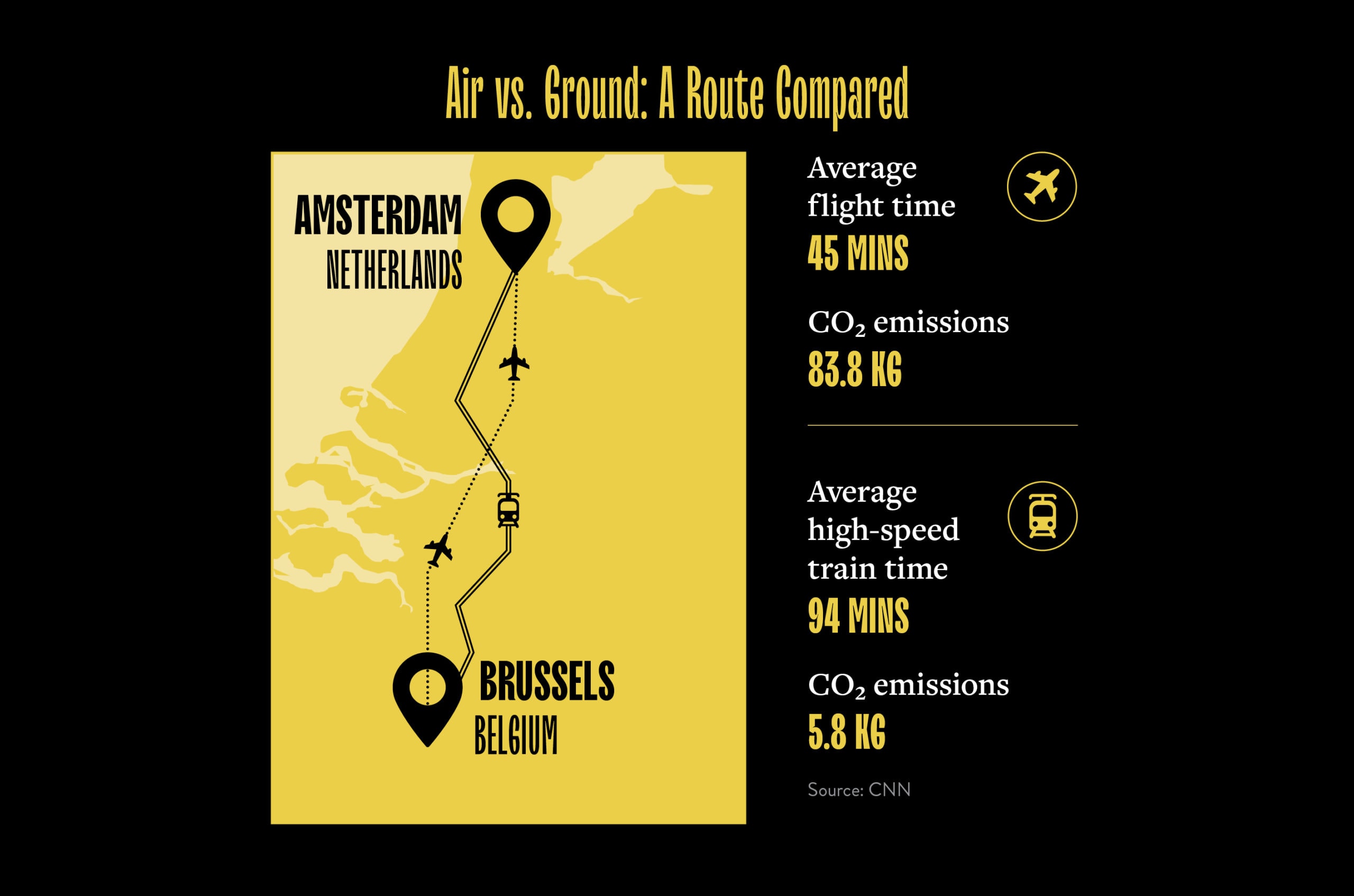

The video was a harbinger for a series of sustainability measures that followed, including the introduction of biofuel for flights out of Schiphol Airport, a robust fleet renewal plan for improved fuel efficiency and a much-lauded pivot to ground transportation. As of March 29, one of KLM’s five daily flights between Amsterdam and Brussels will be replaced by a 93-minute high-speed Thalys train service, with plans to do the same with routes to London, Berlin, Paris and Düsseldorf. The airline says replacing the Amsterdam-Brussels flight will yield 3.2 metric tons of CO‚‚ savings per flight, and 15,500 per year.

“We have only one planet, and when it comes to the future of sustainable aviation, the expectations are sky-high. No one wins in a world that loses.” – Esmée van Veen, KLM

Turning to high-speed rail is an astute move, especially in Europe where extensive infrastructure supports it, says Swedish academic Stefan Gössling, an expert in sustainable tourism who spoke with a mixture of optimism and apprehension about the industry’s future. “It shouldn’t matter to airlines where they earn their money in the transport system; the important thing is that we have a transport system that is functional,” he says. “The question is, how can we get airline CEOs to consider becoming engaged in different transport modes so that when we are building a high-speed railway system that takes capacity away from them, they don’t feel like they’re losing out?” Dr. Leader calls KLM’s initiative and similar integrations with bus networks in the US “beginning steps,” adding that, “Over the next decade, airlines will tie into end-to-end journey management. This will include every new mode of efficient transportation imaginable.”

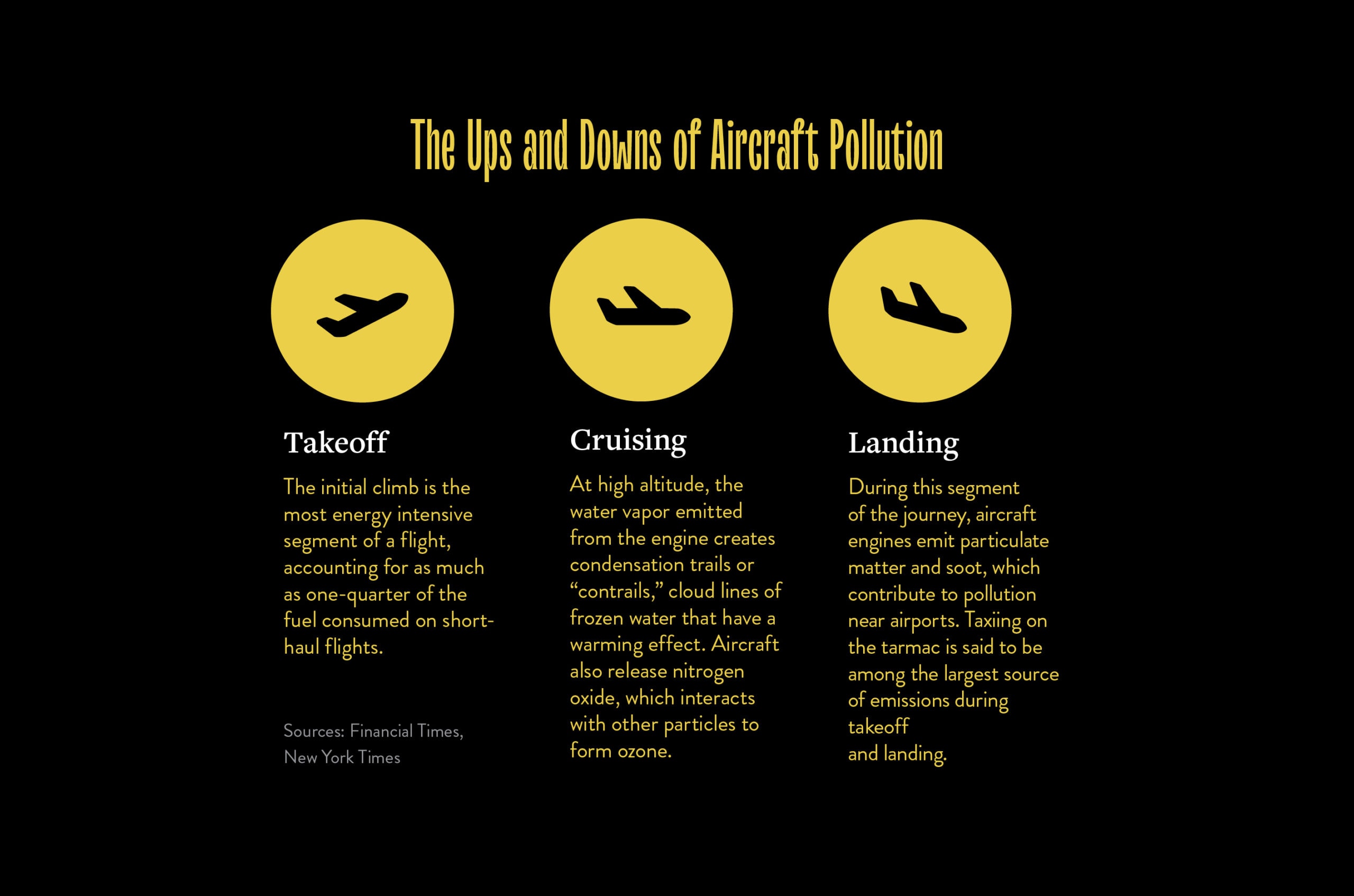

Short-haul flights are logical targets for replacement, especially since they have been criticized for their disproportionately high carbon footprint. Takeoff is the most energy-intensive part of the journey, and when a journey is short it can make up as much as 25 percent of fuel consumption. Since aircraft become more fuel efficient while cruising, longer journeys are generally more fuel efficient per mile traveled.

“Airlines will have to think carefully about how to construct those messages to avoid their being perceived as greenwashing.” – Stefan Gassling, Swedish academic

The logic has some holes. For one, the extra fuel carried on ultra long-haul flights adds enough weight that the flight’s fuel efficiency is reduced. Secondly, tallying carbon per mile can belie the reality that the total carbon emitted by long-haul flights remains more damaging than that on shorter ones: A flight from London to Melbourne, for instance, has approximately 15 times the impact of one from London to Barcelona. And lastly, replacing a flight with a train service is only environmentally responsible if the ground service actually cuts emissions. (According to scientists, certain commuter rail lines operate on diesel or electricity generated from fossil fuels that are more carbon intensive than the airborne alternative.) The other question to ask is what happens to the empty airport slot. In the case of KLM’s forthcoming opening at Schiphol, van Veen admits, “By replacing short-haul flights with rail services, scarce slots can be used for services to long-haul destinations.”

Nonetheless, KLM’s Fly Responsibly campaign presents a fresh model for engaging with climate-conscious consumers who may no longer be as responsive to flash sales and 24-hour-stopover promotions, which Cohen says incite “flippant flying” – something airlines, especially those on the low-cost spectrum, have historically pandered to. “The opposite of that kind of flippancy is what KLM is doing in terms of highlighting responsibility – similar to what alcohol companies do when they say to drink responsibly. But airlines will have to think carefully about how to construct those messages to avoid their being perceived as greenwashing,” he says.

NOT ALL MADE EQUAL

One airline that’s tried to adjust its cadence is Ryanair, most recently referring to itself as the “greenest/cleanest airline” and releasing an advert depicting one of its aircraft crossing above an emerald-green pasture accompanied by the words “Europe’s Lowest Fares, Lowest Emissions Airline.” The media backlash was swift, with a Telegraph headline reading “A ‘low’ emissions airline? Ryanair must think we’re idiots,” and one published on Wired, titled “Sorry Ryanair, there’s no such thing as a green airline.”

Ryanair, which had just recently joined nine coal plants on the list of the top 10 carbon emitters in Europe, rooted its claims in one key metric: CO‚‚ released per passenger kilometer. And according to that metric, Ryanair’s 67 grams of CO‚‚ per passenger kilometer indeed seems paltry compared to that of a flag carrier’s, which is about double. High load factors and high-density cabins (smaller seats mean more passengers) moved by the same amount of fuel are largely to thank, and armed with these figures, Ryanair and its low-cost kin Wizz Air and Norwegian Air are goading the industry into eliminating the premium cabins of their legacy rivals.

“Business class is the worst thing for the environment. We need to do something about that,” said Ryanair CMO Kenny Jacobs. Norwegian issued a similar comment, and Wizz Air went as far as to release a clip calling for a ban on business-class cabins: “We think you’re doing great… harm to our planet… Are all those empty seats worth the damage they cause?” the video’s narrator asks.

“Business class is the worst thing for the environment. We need to do something about that.” – Kenny Jacobs, Ryanair

According to research from the World Bank, emissions associated with flying business class are about three times higher than those from flying economy, with the carbon footprint of a passenger in first class amounting to approximately nine times as much. But this reasoning is a slippery slope, Dr. Leader warns: “Hypothetically, if regulations allowed it, a new ‘standing-room-only’ airline could come online and attack Wizz Air, Ryanair and Norwegian for being carbon-inefficient for allowing people to sit. In my opinion, airlines attacking other airlines for a class of service they do not offer does not serve the industry or our global passengers.”

Lufthansa Group CEO Carsten Spohr isn’t ready to let LCCs off the proverbial hook either. “Flights for less than $10 shouldn’t exist … [they] are economically, ecologically and politically irresponsible,” he said in an interview with Swiss newspaper NZZ am Sonntag this past summer, further supported by research by Gassling and others showing that impossibly low fares (sometimes not even covering fuel and handling fees) have a tendency to stimulate air travel that would perhaps not have otherwise occurred.

A recent comment from Ryanair Holdings group CEO Michael O’Leary seems to support the claim: “Should everyone be flying around Europe for $9 Probably not. But if that’s what it takes to get people to fly to Frankfurt on a Tuesday in November, we’ll take it.” Ryanair serves over 130 million passengers per year with its no-frills approach, making it one of Europe’s largest airlines.

COUNTING CARBON, NOT MILES

Amid the finger-pointing, the industry has said little on the topic of frequent-flyer programs, which at their core are designed to reward flying and encourage more of it. Loyal customers love them, and they remain an important source of revenue for carriers. “Airlines worldwide make an average of just over $5 per passenger flight, and without ancillary revenue, including frequent-flyer programs, airlines would not be profitable,” Dr. Leader says. According to him, such programs aren’t incentivizing as much travel as one might think either: Studies indicate that over half of all flyers do not collect miles, and 40 percent of frequent flyers who do collect them never redeem them.

Nonetheless, Dr. Richard Carmichael, research associate at Imperial College London’s Centre for Environmental Policy, recently published a report for the Committee on Climate Change, arguing that frequent-flyer programs, which he contends compel participants to engage in mileage runs to maintain their privileged status, should be replaced by a frequent-flyer levy, which in the UK would discourage flying among the 15 percent of the population estimated to be responsible for 70 percent of passenger air travel. “Given the small number of frequent flyers, most of the population would be unaffected by the levy, and families would not be penalized for an annual holiday in the sun,” he says.

Nonetheless, Dr. Richard Carmichael, research associate at Imperial College London’s Centre for Environmental Policy, recently published a report for the Committee on Climate Change, arguing that frequent-flyer programs, which he contends compel participants to engage in mileage runs to maintain their privileged status, should be replaced by a frequent-flyer levy, which in the UK would discourage flying among the 15 percent of the population estimated to be responsible for 70 percent of passenger air travel. “Given the small number of frequent flyers, most of the population would be unaffected by the levy, and families would not be penalized for an annual holiday in the sun,” he says.

While the call for a ban on these programs hasn’t been heeded, conventional fly-to-fly loyalty schemes have been evolving for years, with many miles issued for non-flying activities and lots of people engaging with frequent-flyer programs without taking flight.

Last spring, Lufthansa Innovation Hub launched RYDES, a program that rewards all forms of mobility, including air travel (current airline participants include Lufthansa, Eurowings, KLM, Ryanair and easyJet), public transportation, bike sharing and even e-scooters. Recently, the program has integrated a new feature called Changemaker, a CO‚‚ tracking tool providing users with a transparent overview of their personal CO‚‚ consumption. “Sustainability has always been a part of our product, and it is getting increasingly important. With the new product feature, we help users develop awareness of their mobility-related CO‚‚ emissions,” says René Braun, project lead at RYDES.

In July, Qantas began weaving carbon concern directly into its loyalty infrastructure, with “Fly Carbon Neutral,” which rewards flyers for carbon offsetting to the tune of 10 Qantas points per $1 spent. The program is nonprofit, with the money going to projects selected by the airline, including a fire-abatement initiative in Western Australia; rebuilding wetlands in Babinda, upstream from the Great Barrier Reef; and the Rarakau Rainforest Conservation Project, in

New Zealand. According to Qantas, the number of loyalty program members offsetting their flights has surged by 15 percent since the program took off.

“We recognize that offsetting is only an interim measure, but we want to take action on our carbon emissions now.” – Johan Lundgren, easyJet

With ICAO’s Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), which aims to cap net emissions at 2020 levels, coming into effect next year, one can expect a growing number of carbon-offset pledges from airlines in the works. In the past several months, both British Airways and JetBlue have committed to going carbon neutral on domestic flights, and easyJet has announced a $32-million plan to become the world’s first major airline to operate net-zero-carbon flights across its entire network.

However, climate activists and campaign groups doubt the viability of these initiatives, saying that carbon offsetting (many industries’ bulwark against environmentalists) is tantamount to paying others to be allowed to keep polluting. Offsetting schemes have also been criticized for taking time to come into effect (trees don’t grow overnight), being temporary (trees can be cut down or burnt) and for giving consumers the unrealistic impression of an immediate antidote.

In a comment that anticipates the deluge of criticism he would receive, Johan Lundgren, easyJet’s chief executive, acknowledged that the move falls short. “We recognize that offsetting is only an interim measure, but we want to take action on our carbon emissions now,” he said. “Aviation will have to reinvent itself as quickly as it can.” Lundgren is right: In the absence of tenable low-carbon electric technologies and widespread implementation of biofuels, becoming green is not yet an option. But in the interim, being responsible can be.

“Carbon Conscious” was originally published in the 10.1 February/March issue of APEX Experience magazine.